Last year Commodore USA announced a deal with Commodore Licensing to release a PC all-in-one, cased in an exact replica of the Commodore 64 which was originally released back in 1982. That new PC has now been revealed.  Housed in the classic beige chassis of the original, you’ll find a modern mini-ITX PC motherboard with an Intel dual-core 525 Atom processor and the latest Nvidia Ion2 graphics chipset. It has 2GB of DDR3 RAM (expandable to 4GB) and it can output 1080p HD with its HDMI slot.  There are a few features that the 80s classic was lacking – including a optical drive (with a Blu-ray option) and a multi-card reader and USB slots. There’s Wi-Fi on board, as well as DVI and VGA output. You can also choose to boot the PC into Commodore emulator mode for some 8-bit gaming, or run Workbench 5. Currently there are no price or availability details at this time.

Color TV Game 6 is the first Color TV Game ever released. It was released only in Japan in 1977, and featured only one game; Light Tennis, which looked and played much like Pong. The game featured 6 different modes, such as the original, as well as others with different ways to play pong such as ones with obstacles. In Japan, it sold over a million copies and was successful enough to warrant a sequel titled Color TV Game 15. Gameplay Up to two players could play this game, though there were no detachable controllers, something Nintendo would fix in future titles. Instead, there were two knobs on the console that the players could turn to move their paddle up and down. Similar to Pong, players would hit the ball back and fourth, making sure it doesn't go past their paddle. The game had bright colors as opposed to the black and white coloring of Pong. As the game's name implies, there were six game modes, each one with a minor alteration. Development The Color TV Game 6 was Nintendo's first home console designed in-house. It was built in collaboration with the Mitsubishi Company after the car maker's deal with Systek fell through after their company dissolved. Mitsubishi went to Nintendo's president Hiroshi Yamauchi in hopes of striking a deal and managed to do so successfully. Yamauchi knew that his system had to be cheap since he (accurately) assumed that the other systems on the market failed due to their steep prices. This payed off, as over 350,000 people in the country purchased a Color TV Game 6. Perhaps even more surprising is that the Color TV Game 15, which contained over twice the amount of games as the Color TV Game 6 (but at more of a cost) sold over 700,000 units in Japan. Every CTVG6 unit sold actually lost Nintendo money. Apparently, in order to accumulate a profit, Nintendo would have had to sell the system for 12,000 yen. In order to find away around this, the Color TV Game 15 which, as previously indicated, sold around twice the amount as the Color TV Game 6, was released alongside it. The Color TV Game 15 featured nine more games, detachable controllers and a slicker design. Eventually it appears as if Nintendo succeeded in lowering the cost of development since they reduced the price of the Color TV Game 6 to 5,000 yen and included an AC adapter.

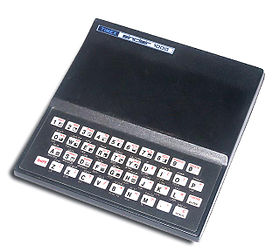

The Sinclair ZX81 was small, black with only 1K of memory, but 30 years ago it helped to spark a generation of programming wizards. Packing a heady 1KB of RAM, you would have needed more than 50,000 of them to run Word or iTunes, but the ZX81 changed everything. It didn't do colour, it didn't do sound, it didn't sync with your trendy Swap Shop style telephone, it didn't even have an off switch. But it brought computers into the home, over a million of them, and created a generation of software developers. Before, computers had been giant expensive machines used by corporations and scientists - today, they are tiny machines made by giant corporations, with the power to make the miraculous routine. But in the gap between the two stood the ZX81. Continue reading the main story “ Start Quote If you had an extension pack you had to hold it in place with Blu-Tack, because if it wobbled a bit you'd lose everything” End Quote Richard Vanner It wasn't a lot of good at saving your work - you had to record finished programming onto cassette tape and hope there was no tape warp. It wasn't even that good at keeping your work, at least if you had the 16K extension pack stuck precariously into the back. One wobble and your day was wasted. But you didn't have to build it yourself, it looked reassuringly domestic, as if it would be happy sitting next to your stereo, and it sold in WH Smiths, for £69.95.  "It started off a proud tradition of teenage boys persuading their parents to buy them kit with the excuse that it was going to be educational," recalls Gordon Laing, editor of the late Personal Computer World and author of Digital Retro. "It was no use for school at all, but we persuaded our parents to do it, and then we just ended up playing games on them." The ZX81 was a first taste of computing for many people who have made a career out of it. Richard Vanner, financial director of The Games Creators Ltd, is one. "I was 14," he says, "and my brain was just ready to eat it up. There was this sense of 'Wow, where's this come from?' You couldn't imagine a computer in your own home. The machine could get very hot, recalls Vanner. "The flat keyboard was hot to type on. If you had an extension pack you had to hold it in place with Blu-Tack, because if it wobbled a bit you'd lose everything. You'd have to unplug the TV aerial, retune the TV, and then lie down on the floor to do a bit of coding. And then save it onto a tape and hope for the best. "But because it was so addictive, you didn't mind all these issues." Many a teenaged would-be programmer spent hours poring over screeds of code in magazines. The thermal printer was loaded with a shiny toilet roll "It would take hours and hours to type in, and if you made just one mistake - which might have been a typing error in the magazine - it didn't work," says Laing. "Also there was the thermal printer for it, with shiny four-inch paper like till receipts, and as soon as you got your fingers on it you could wipe it off. One fan site described it as 'a rather evil sort of toilet roll'." In fact, the very limitations of the ZX81 are what built a generation of British software makers. Offering the ultimate in user-frostiness, it forced kids to get to grips with its workings. "I taught myself to program with the manual," says Vanner, "which was quite difficult. It was trial and error, but I got things working. Then magazines started to come out, and there we were, game-making with 1K." That lack of memory, similarly, was a spur to creativity. "Because you had to squeeze the most out of it," says Vanner, "it forced you to be inventive. Someone wrote a chess game. How do you do chess with 1024 bytes? Well the screen itself took up a certain amount of memory, so they loaded the graphics onto the screen from the tape. There was no programme for that, but people got round these things with tricks." Continue reading the main story A programmer inspired Charles Cecil, managing director of Revolution Software which produced the Broken Sword and Dr Who games, discovered computing at university when a friend invited him to write a text adventure game for the ZX81. "It took two or three days and was quite fun. It was called Adventure B. He sold it and it did really well. He'd actually looked at the memory in the ROM, and worked out what was going on so he could write much more efficient code. "We did the most extraordinary things - a game that really played chess in 1K. The Americans had the Commodore 64 [with 64K] but we were forced to programme very very tightly and efficiently. That's defined our style of programming up until today. The UK has some of the best programmers in the world, thanks to those roots." Some feel that the amount of memory on today's computers can make programmers lazy and profligate. Sir Clive Sinclair himself told the Guardian last year: "Our machines were lean and efficient. The sad thing is that today's computers totally abuse their memory - totally wasteful, you have to wait for the damn things to boot up, just appalling designs. Absolute mess! So dreadful it's heartbreaking." The name combined the two most futuristic letters in the alphabet with a number that rooted it in the present day - though that doesn't seem to have been particularly deliberate. The designer Rick Dickinson says they named its predecessor, the previous year's ZX80, after its processor, the Zilog Z80, with an added X for "the mystery ingredient". Dickinson visited Dixons to consider which existing products it should look like, he says. "But I don't know that I came up with any answers. Most of this stuff was just blundering through, and hitting on something that just seemed right. "We wanted it to be small, black and elegantly sculpted. Beyond that the main thing was the cost, so the keyboard had just three parts compared to hundreds today. And some keys had six or even seven functions, so there was the graphics exercise of getting that amount of data onto the keypad. But why it so captured the public imagination, Dickinson finds hard to say. "They liked the design of it, and they liked the price, but beyond that you'd have to ask a psychologist. It created its own market. "No-one knew they wanted a computer. It was just the right product, at the right time, at the right price."

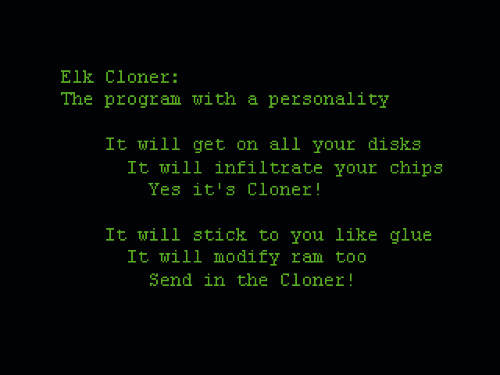

In the early years floppy disks (removable media) were in fact the prevalent method used to spread viruses. Bulletin boards and online software exchange systems emerged as major channels for the spread of viruses in the late 80s. Ultimately of course, the internet in all its forms became the major source of infection. Our timeline for PC Virus history, is as follows:1944In Theory John von Neumann – the brilliant mathematician who helped bring us nuclear energy, game theory and quantum theory’s operating mechanics – theorized about the existence of computer viruses as early 1944. In a series of lectures called “Theory of self-reproducing automata” von Neumann contemplated the difference between computers and the human mind, and also about the possibility of self-relicating computer code. Considering the modern computer virus is, essentially, self-replicating computer code adds to von Neumann’s impressive academic achievements, as such code is commonplace today. 1982The first externally released virus is thought to be 'Elk Cloner', written by Rich Skrenta. It infected Apple DOS 3.3 computers, and spread via floppy disk. This, of course, opened the way for viruses to really spread. A program called Elk Cloner, written by a 15-year-old, spread itself via floppy disks. Like Creeper it really didn’t do a lot of damage; it would occasionally display a poem taunting the end-user and simply spread itself.  Rich Skrenta, the virus’s creater, called it “some dumb little practical joke.” That may have been so to him, but viruses would soon grow far beyond that. The 1980s would see viruses appear for all the major platforms including IBM, Amiga, and even BSD UNIX. The diversity of computer operating systems on the market prevented viruses from spreading too quickly, however. That would change in the 90s. 1983The term 'computer virus' begins to emerge. This is often credited to Fred Cohen of the University of Southern California. 1986Early PC viruses start to appear. One of the first, emerging from Pakistan, is known as the 'Brain' and is a 'boot sector' virus (floppy disk). 1987The first 'file' viruses begin to appear (largely affecting the essential system file command.com). 1988The ARPANET worm, written by Robert Morris, disables approx 6,000 computers on the network. The well known (at the time) Friday the 13th virus is released in this year. The Cascade virus, thought to be the first encrypted virus, is discovered. is found 1989The AIDS trojan appears. It was fairly unique at the time because it demanded payment for removal. 1990Anti-virus software begins to appear 1991Norton Anti-Virus software is released by Symantec. The first widely spread polymorphic virus (one which changes its appearance as it spreads), "Tequila", is released. 1992Well over 1,000 viruses are now thought to exist. 1994The first major virus hoax, known as "Good Times" surfaces 1995The first major 'Word' virus emerges, known as "Concept" 1999The "Melissa" virus, written by David L. Smith, infects countless thousands of PCs (estimated damage = $80 million). It replicates by sending copies of itself to addresses in the Microsoft Outlook address book. The author is subsequently jailed for 20 months. 2000In May of this year, the 'I Love You' virus, written by a Filipino student, infects millions of PCs. It is similar to "Melissa" but sends passwords back over the network. 2001In July, the Code Red worm infects thousands of Windows NT/2000 servers, causing $2 billion in damages (estimated) 2003In January the "Slammer" worm spreads at the fastest rate thus far, and infects hundreds of thousands of PCs. There are more MS-DOS/Windows viruses than all other types of viruses combined (by a large margin). Estimates of exactly how many there are vary widely and the number is constantly growing. In 1990, estimates ranged from 200 to 500; then in 1991 estimates ranged from 600 to 1,000 different viruses. In late 1992, estimates were ranging from 1,000 to 2,300 viruses. In mid-1994, the numbers vary from 4,500 to over 7,500 viruses. In 1996 the number climbed over 10,000. 1998 saw 20,000 and 2000 topped 50,000. It's easy to say there are more now. Indeed, in April 2008, the BBC reported that Symantec now claims "that the security firm's anti-virus programs detect to 1,122,311" viruses and that "almost two thirds of all malicious code threats currently detected were created during 2007." The confusion exists partly because it's difficult to agree on how to count viruses. New viruses frequently arise from someone taking an existing virus that does something like put a message out on your screen saying: "Your PC is now stoned" and changing it to say something like "Donald Duck is a lie!". Is this a new virus? Most experts say yes. But, this is a trivial change that can be done in less than two minutes resulting in yet another "new" virus. More confusion arises with some companies counting viruses+worms+Trojans as a unit and some not. Another problem comes from viruses that try to conceal themselves from scanners by mutating. In other words, every time the virus infects another file, it will try to use a different version of itself. These viruses are known as polymorphic viruses. One example, the Whale (an early, huge, clumsy 10,000 byte virus), creates 33 different versions of itself when it infects files. At least one vendor counted this as 33 different viruses on their list. Many of the large number of viruses known to exist have not been detected in the wild but probably exist only in someone's virus collection. David M. Chess of IBM's High Integrity Computing Laboratory reported in the November 1991 Virus Bulletin that "about 30 different viruses and variants account for nearly all of the actual infections that we see in day-to-day operation." In late 2007, about 580 different viruses, worms, and Trojans (and some of these are members of a single family) account for all the virus-related malware that actually spread in the wild. To keep track visit the Wildlist, a list which reports virus sightings. How can there be so few viruses active when some experts report such high numbers? This is probably because most viruses are poorly written and cannot spread at all or cannot spread without betraying their presence. Although the actual number of viruses will probably continue to be hotly debated, what is clear is that the total number of viruses is increasing, although the active viruses not quite as rapidly as the numbers might suggest. SummaryBy number, there are well over 100,000 known computer viruses. Only a small percentage of this total number account for those viruses found in the wild, however. Most exist only in collections. This is in no way complete, but a brief outline of the start and progression of the virus phenomena. Do you have any cool stories from the early history of computer viruses? Please share!

Why a Computer History Museum? - Code: Select all

http://www.computerhistory.org/

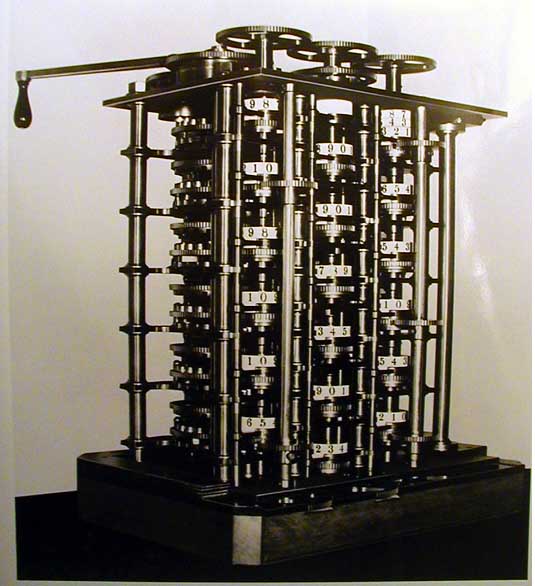

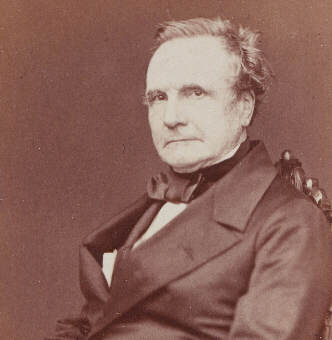

I highly recommend this site for an interesting experience !  Humans have been creating tools since before recorded history. For many centuries, most tools served to amplify the power of the human body. We call the period of their greatest flowering the Industrial Revolution. In the last 150 years we have turned to inventing tools that amplify the human mind, and by doing so we are creating the Information Revolution. At its core, of course, is computing. “Computer” was once a job title. Computers were people: men and women sitting at office desks performing calculations by hand, or with mechanical calculators. The work was repetitive, slow, and boring. The results were often unreliable. In the mid 1800s, the brilliant but irascible Victorian scientist Charles Babbage contemplated an error-filled book of navigation tables and famously exclaimed, “I wish to God these calculations had been executed by steam!” Babbage designed his Difference Engine to calculate without errors, and then, astoundingly, designed the Analytical Engine — a completely programmable computer that we would recognize as such today. Unfortunately he failed to build either of those machines.  Charles babbage Automatic computation would have to wait another hundred years. That time is now. The Universal MachineThe computer is one of one of our greatest technological inventions. Its impact is—or will be—judged comparable to the wheel, the steam engine, and the printing press. But here’s the magic that makes it special: it isn’t designed to do a specific thing. It can do anything. It is a universal machine. Software turns these universal machines into a network of ATMs, the World Wide Web, mobile phones, computers that model the universe, airplane simulators, controllers of electrical grids and communications networks, creators of films that bring the real and the imaginary to life, and implants that save lives. The only thing these technological miracles have in common is that they are all computers. We are privileged to have lived through the time when computers became ubiquitous. Few other inventions have grown and spread at that rate, or have improved as quickly. In the span of two generations, computers have metamorphosed from enormous, slow, expensive machines to small, powerful, multi-purpose devices that are inseparably woven into our lives. A “mainframe” was a computer that filled a room, weighed many tons, used prodigious amounts of power, and took hours or days to perform most tasks. A computer thousands of times more powerful than yesterday’s mainframe now fits into a pill, along with a camera and a tiny flashlight. Swallow it with a sip of water, and the “pill” can beam a thousand pictures and megabytes of biomedical data from your vital organs to a computer. Your doctor can now see, not just guess, why your stomach hurts. The benefits are clear. But why look backward? Shouldn’t we focus on tomorrow? Why Computer History?History places us in time. The computer has altered the human experience, and changed the way we work, what we do at play, and even how we think. A hundred years from now, generations whose lives have been unalterably changed by the impact of automating computing will wonder how it all happened—and who made it happen. If we lose that history, we lose our cultural heritage. Time is our enemy. The pace of change, and our rush to reach out for tomorrow, means that the story of yesterday’s breakthroughs is easily lost. Compared to historians in other fields, we have an advantage: our subject is new, and many of our pioneers are still alive. Imagine if someone had done a videotaped interview of Michelangelo just after he painted the Sistine Chapel. We can do that. Generations from now, the thoughts, memories, and voices of those at the dawn of computing will be as valuable. But we also have a disadvantage: history is easier to write when the participants are dead and will not contest your version. For us, fierce disagreements rage among people who were there about who did what, who did it when, and who did it first. There are monumental ego clashes and titanic grudges. But that’s fine, because it creates a rich goldmine of information that we, and historians who come after us, can study. Nobody said history is supposed to be easy. It’s important to preserve the “why” and the “how,” not just the “what.” Modern computing is the result of thousands of human minds working simultaneously on solving problems. It’s a form of parallel processing, a strategy we borrowed to use for computers. Ideas combine in unexpected ways as they built on each other’s work. Even simple historical concepts aren’t simple. What’s an invention? Breakthrough ideas sometimes seem to be “in the air” and everyone knows it. Take the integrated circuit. At least two teams of people invented it, and each produced a working model. They were working thousands of miles apart. They’d never met. It was “in the air.” Often the process and the result are accidental. “I wasn’t trying to invent an integrated circuit,” Bob Noyce, co-inventor of the integrated circuit, was quoted as saying about the breakthrough. “I was trying to solve a production problem.” The history of computing is the history of open, inquiring minds solving big, intractable problems—even if sometimes they weren’t trying to. The most important reason to preserve the history of computing is to help create the future. As a young entrepreneur, the story goes, Steve Jobs asked Noyce for advice. Noyce is reported to have told him that “You can’t really understand what’s going on now unless you understand what came before.” Technology doesn’t run just on venture capital. It runs on adventurous ideas. How an idea comes to life and changes the world is a phenomenon worth studying, preserving, and presenting to future generations as both a model and an inspiration. History Can Be FunBesides—computer history can be fun. An elegantly designed classic machine or a well-written software program embodies a kind of truth and beauty that give the qualified appreciative viewer an aesthetic thrill. Steve Wozniak’s hand-built motherboard for the Apple I is a beautiful painting. The source code of Apple’s MacPaint program is poetry: compressed, clear, with all parts relating to the whole. As Albert Einstein observed, “The best scientists are also artists.” Engineers have applied incredible creativity to solve the knotty problems of computing. Some of their ideas worked. Some didn’t. That’s more than ok; it’s worth celebrating. Silicon Valley understands that innovation thrives when it has a healthy relationship with failure. (“If at first you don’t succeed...”) Technical innovation is lumpy. It’s non-linear. Long periods of the doldrums are smashed by bursts of insight and creativity. And, like artists, successful engineers are open to the happy accident. In other cultures, failure can be shameful. Business failure can even send you to prison. But here, failure is viewed as a possible prelude to success. Many great technology breakthroughs are inspired by crazy ideas that bombed. We need to study failures, and learn from them. Where are all the museums?Given the impact of computing on the human experience, it’s surprising that the Computer History Museum is one of very few institutions devoted to the subject. There are hundreds of aircraft, railroad, and automobile museums. There are only a handful of computer museums and archives. It’s difficult to say why. Maybe the field is too new to be considered history. We are proud of the leading role the Computer History Museum has taken in preserving the history of computing. We hope others will join us. The kernel of our collection formed in the 1970s, when Ken Olsen of the Digital Equipment Corporation rescued sections of MIT’s Whirlwind mainframe from the scrap heap. He tried to find a home for this important computer. No institution wanted it. So he kept it and began to build his own collection around it. Gordon Bell, also at DEC, joined the effort and added his own collection. Gordon’s wife, Gwen, attacked with gusto the task of building an institution around them. They saw, as others did not, that these early machines were important historical artifacts—treasures—that rank with Gutenberg’s press. Without Olsen and the Bells, many of the most important objects in our collection would have been lost forever. Bob Noyce would have understood the errand we are on. Leslie Berlin’s book The Man Behind The Microchip tells the story of Noyce’s comments at a family gathering in 1972. He held up a thin silicon wafer etched with microprocessors and said, “This is going to change the world. It’s going to revolutionize your home. In your own house, you’ll all have computers. You will have access to all sorts of information. You won’t need money any more. Everything will happen electronically.” And it is. We are living in the future he predicted. The Computer History Museum wants to preserve not just rare and important artifacts and the stories of what happened, but also the stories of what mattered, and why. They are stories of heretics and rebels, dreamers and pragmatists, capitalists and iconoclasts—and the stories of their amazing achievements. They are stories of computing’s Golden Age, and its ongoing impact on all of us. It is an age that may have just begun.

While Xbots and the Sony Defence Force argue among themselves, and Wii-mers (Wii-ers?) throw ever more ridiculous shapes pretending to play the tambourine or something, there is another group of gamers who quietly, happily, enjoy the best gaming platform yet invented - the PC. And while, granted, some huge percentage of PCs are never used for anything other than Outlook and basic web, PCs remain the most flexible and happiest way to game. And, unlike Wii Sports, it won't cause you permanent physical damage. 1. Mouse and keyboard support Well, duh. Console kids who have grown up with a controller in hand might argue, but there's still no better way of playing just about any game in any genre – not just shooters – than the combination of keyboard and mouse. It just works, offering orders of magnitude more precision and speed than fiddly analogue sticks. 2. High screen resolutions While Microsoft and Sony scream about 'true HD' in their games – but in many cases don't actually deliver it – the PC has been happily running games at 1080p and above for yonks. In fact, the near-HD default res of 1,280x1,024 is very 2001; even a medium rig can handle 1,600x1,200 or more these days. 3. Free mods Were you a raw naif, you might be forgiven for thinking that LittleBigPlanet et al single-handedly invented the idea of (nnnggh) 'user generated content'. But guess what? PC gamers have been coding mods (modifications) such as add-ons, total conversions, unofficial levels and all manner of other gubbins for… well, pretty much forever. And then distributing it for free, for the sheer love of it. 4. Upgradeable hardware With the aforementioned higher resolutions and textures, chances are a new PC game already looks better than its console counterpart right now. But even if you can't run it with all the visuals tweaked to the max, processor and graphic cards prices drop so quickly that it's hardly bank-breaking to refit your rig in a year or so, for better graphics and more speed. 5. Cheaper games Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo's licensing and publishing costs inevitably drive up the cost of every single game released, and even pre-owned games tend to be far pricier than the PC equivalent. World of Warcraft and EVE Online are only available for the PC - need we say more?  World of Warcraft  Eve Online 6. You're not tied to one online service Imagine not having to rely on a single, central server such as Xbox Live or PlayStation Network whenever you go online. Imagine not having to suffer downtimes, silly licensing agreements, or daft console-restricting DRM. Oh wait… that's the PC online, isn't it? 7. No extra dosh needed for playing online Okay, this only applies to Xbox Live, but who's to say that Sony might not start charging for PSN as it keeps haemorrhaging money? And yes, Xboxers can use the free Silver service, but really – why would you? 8. Unlimited storage space The Xbox 360 is limited to whatever can fit on a DVD (or, if you're unlucky, more than one). The PlayStation 3 has to struggle with turgid Blu-ray access and enforced installs. PC games, meanwhile, just sit happily on the potentially unlimited storage space of your hard drive. Easy. 9. Save game hacking Like modders, PC gamers are rabidly enthusiastic about pulling apart save games and data files, fiddling therein, and finding ingenious ways to cheat or fix corrupted files. Try doing that with your Wii. 10. Unofficial fixes for older games PC games such as Vampire: The Masquerade often get unofficial, free, support long after publishers have gone kaput and official support is abandoned, thanks to the tireless efforts of their fans. Bug fixes, enhancements, new hardware support – it's all there. 11. Abandonware The geek term for 'old games which you can't buy any more'. There are a huge number of classic PC titles out there from years gone by, and many thousands are available to download, legally, for free. 12. No red ring of death Well, you only get this on the Xbox, of course, but the last thing you want your gaming machine to do is to completely konk out. At least when a PC goes wrong, it really goes wrong. Like, with fire and everything (possibly). 13. Emulation Emulation without fear of bricking your machine

ZX Spectrum relaunch: gaming goes back to the future The ZX Spectrum is to be releaunched to celebrate its 30th anniversary. We examine the appeal of retro gaming, the new ZX Spectrum could use a wireless keyboard and an iPhone. As the Sinclair ZX Spectrum approaches its 30th birthday in 2012, the video gaming craze that it began is still going strong. So strong, in fact, that original games developer Elite plans to relaunch the console for a generation of nostalgic gamers. These original enthusiasts are the now middle-aged geeks who are using their mobile phones for games. Gone are the days of plastic joysticks and floppy disks, replaced by iPhones and sophisticated dual-core Google Android devices. In fact, 67pc of smartphone users say that the single biggest use for their handsets is gaming. Texting, web browsing and old-fashioned phone calls account for 54pc, 51pc and 48pc respectively. The new Spectrum will launch against a background of clear enthusiasm for both new, high tech games and consoles, but also for very simple, older games. BlackBerry’s Brick Breaker game is as crucial to millions of users’ attachment to their devices as being able to get email on the go. That sort of enthusiasm means that Elite, the video games developer who was behind a range of the Spectrum’s original hits, has found a new lease of life with “emulators” that allow its games to be played on new devices. Although the company has so far only developed versions for Apple devices, such as the iPod and iPhone, it is also, like many others, planning to put the software on Google Android devices. It is also seeing success with its own modern games such as Paperboy, which was top 20 UK hit on Apple’s App Store. Perhaps surprisingly, the company is also considering how best to put its titles of powerful consoles such as Xbox. Indeed, Nintendo’s new version of 80s classic Donkey Kong, was also accompanied by a limited edition version of the Wii console that included the original Donkey Kong pre-installed. Although the move was a sort of ironic joke, it’s clear that there is an appetite for such games. So titles from Elite such as Test Drive: Off Road and Striker could conceivably receive the same treatment. But what’s the appeal of these games when new technology has brought infiintiely greater capabilities? On forums devoted to such games, two themes emerge: first, it’s about the simplicity of games that are perfect for filling an idle moment on the bus or tuube precisely because they’re not too taxing. Indeed, modern hits such as Paper Toss - which relies on users aiming a scrunched-up piece of paper into a bin – are in fact much less complex than a classic like Space Quest.

PHOTOGRAPH SHOWS: Neil Davidson (Red Gate), Mike Muller (ARM), Jason Fitzpatrick (CfCH) Computer museum backed by ARM, Hauser and Red Gate Cambridge tech heavyweights have joined Business Weekly in a campaign to create a state-of-the-art Cambridge Computing History Museum. Serial tech entrepreneur and co-founder of Acorn Computers, Dr Hermann Hauser, superchip designer ARM Holdings and software pioneer Red Gate have lent their muscle to the quest for a suitable building in Cambridge to house the venture. The vision is to transform around 10,000 sq ft of rented accommodation into an Aladdin’s Cave of computing artefacts. The computing treasure trove would be – initially at least – a more modest version of the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Mass. Jason Fitzpatrick, the man behind the venture, is calling for Cambridge technology businesses to help fund the computing museum going forward. And the Museum's Board of Trustees, of which Fitzpatrick is a member, would be happy to receive more memorabilia for the collection. Jamie Green, of Juniper Real Estate in Cambridge, is helping Jason to find a building of around 10,000 sq ft – or something close to that – or a couple of neighbouring properties adding up to that kind of size to create the showcase and also provide storage facilities. The building would have to be dry and in relatively good condition given the value of the collection in which there are more than 7,000 items – and as close to the city centre as possible to exploit the business and tourism footfalls. ARM has provided some temporary storage for the collection which is currently housed in Haverhill. Red Gate has donated important funding. Hauser commented "It would be wonderful if a Computer Museum was opened in Cambridge to celebrate the many historic milestones Cambridge University and local companies have contributed to." Fitzpatrick, who appeared in the BBC’s Micro Men TV programme, said: “We only have 3,000 sq ft of space in Haverhill so only a fraction of the collection can be displayed. “I am 40 now but my passion for collecting things began when I was 11. I really started building up in earnest about 20 years ago. To be honest I bought far too much and four years ago it was obvious that I would either have to dump all these wonderful machines in lofts or cupboards or honour their legacy by putting them on public display. I chose the latter. “My collection is fairly insignificant compared to all the donations from people all over the country – we have even had donations from the US. “It is a very old collection that traces the history of a technology revolution. These machines date back to the birth of personal computing – my first Sinclair machine is in there and an Acorn BBC Computer – what a contribution Acorn made to this revolution. The Acorn story is incredible. “Some of the early computers are really big machines – like the one Benny Hill wreaked havoc with in the ‘Italian Job’. “The oldest is my Altair 8800 from 1975. Ours is issue number three. It is normally considered the first home computer. We have a Sinclair Spectrum, Commodore 64 and Acorn Atom. “A lot of the early computers came in kit form with just switches and lights. There was no keyboard or mouse. When Steve Job and other major players saw these machines they knew that was definitely not the way they envisaged computing for the future and new generation computers such as the Apple 1 were born. That was Apple’s first product in 1976. “It’s hard to put a value on such a collection. I bought the Altair on ebay for around £10,000 - I put in a binary bid of 11,111 and eventually got it for around the £10k mark - but in historical terms they are priceless really. “Setting nostalgia aside, the microchip made everything possible. From then on, the advent and evolution of personal computers have revolutionised the way we live and work. They have touched practically every aspect of our lives – including medicine – and changed things for ever. “That’s why we are fighting so hard and enlisting support for the Cambridge showcase. Anyone who wants to pitch in with donations, machines or expertise would be most welcome. We are preserving these artefacts for future generations – generations that will be far more switched on to technological advances than most youngsters were when the first personal computers were produced.” The Computing Museum is a registered charity. If you can help with funding, have other suitable memorabilia – or if you have a suitable building for the museum – please get in touch with Jason Fitzpatrick direct on 01440 709794 or via email: - Code: Select all

info@computinghistory.org.uk

|